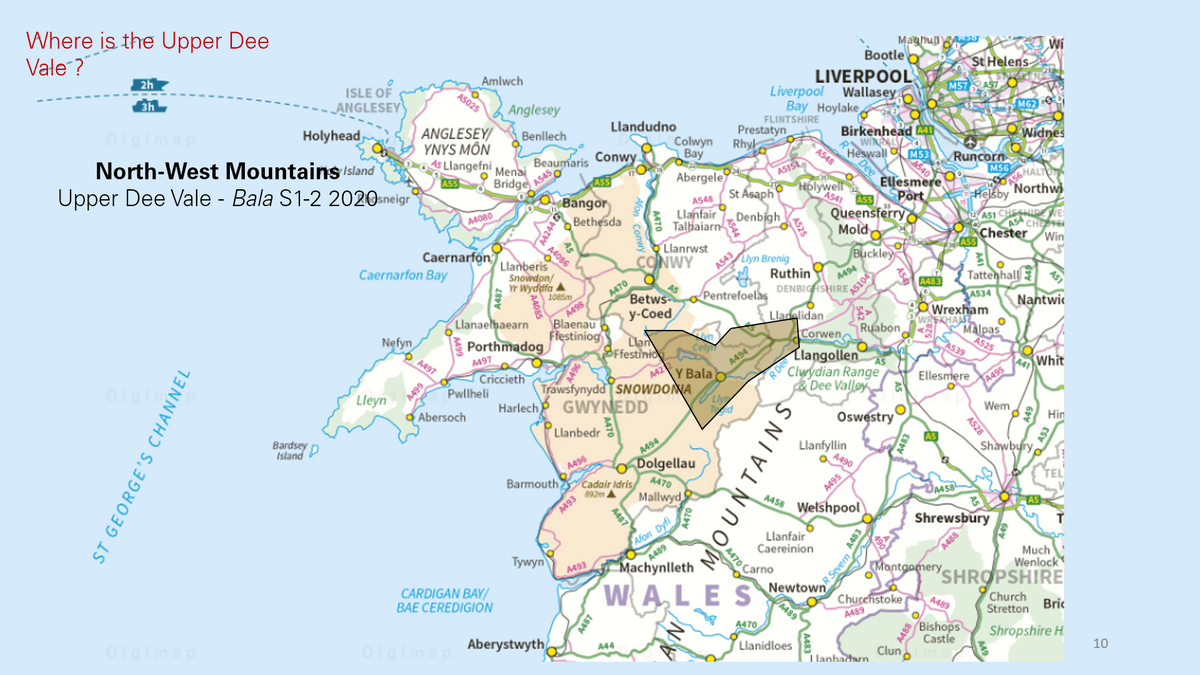

In 2020 I spent the second half of the year focusing on the first study area in my PhD. A place were the mountains meets the sky most part of the year. An area typical of North West Wales Mountains. To do this I moved to Llangollen (a very pretty and lively town, even during the coronavirus crisis) and did my fieldwork further up the Dee valley. It was great and I am grateful to farmers and everyone that allowed me to discover upland farming system (their management, subtelties, drivers...)

Bala Summary – A diverse North-West Wales Upland area with different challenges and opportunities

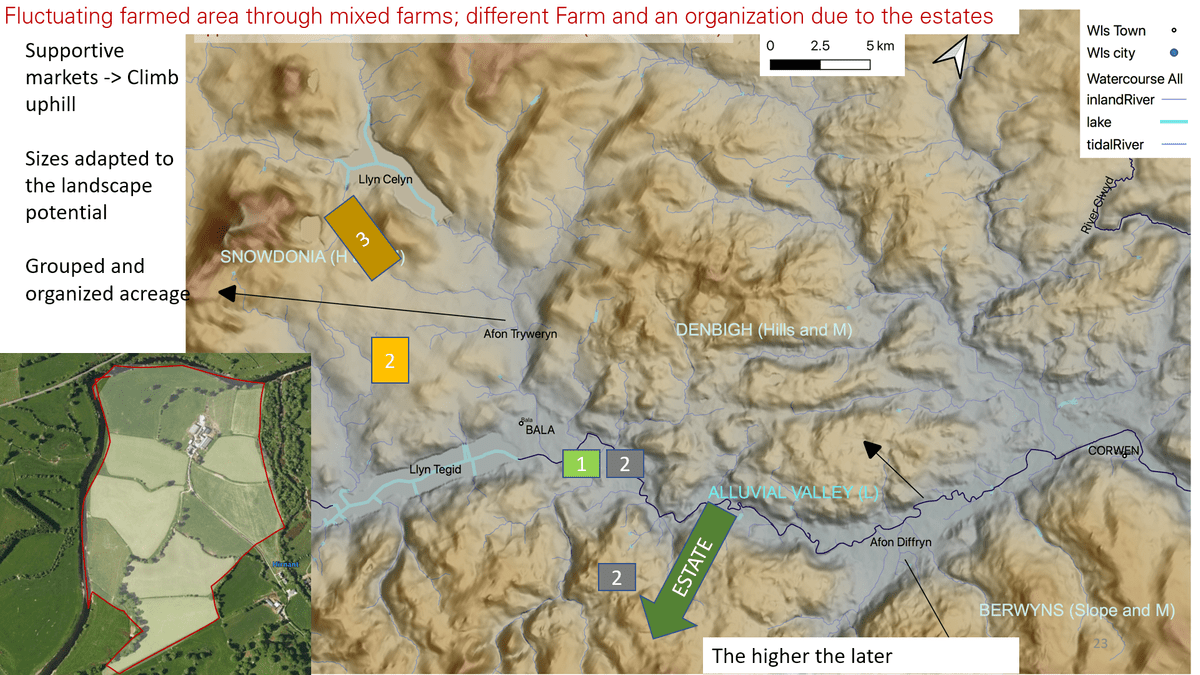

The upper Dee valley catchment is organised around the Dee valley enshrined in the middle of a plateau up to Llyn Tegid and Llyn Celyn. An area relatively isolated, scarcely populated at the border with Snowdonia national park and with a diverse picture illustrating what typical upland landscapes are like.

Ordnance Survey 250K map through digimap

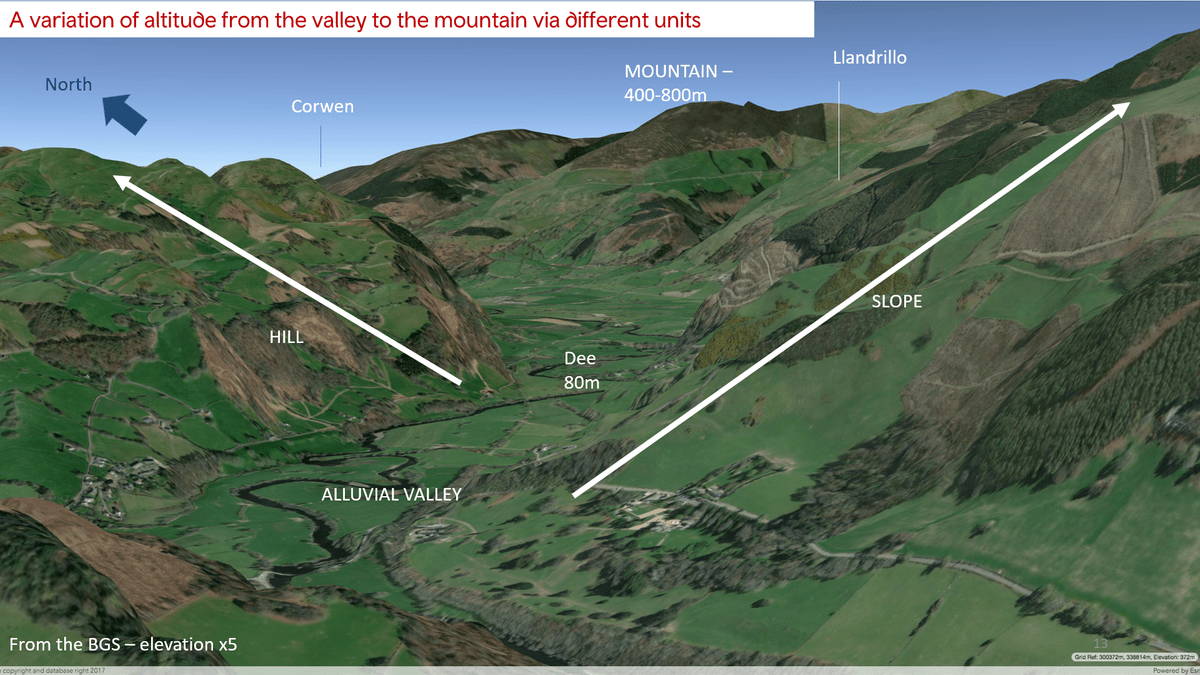

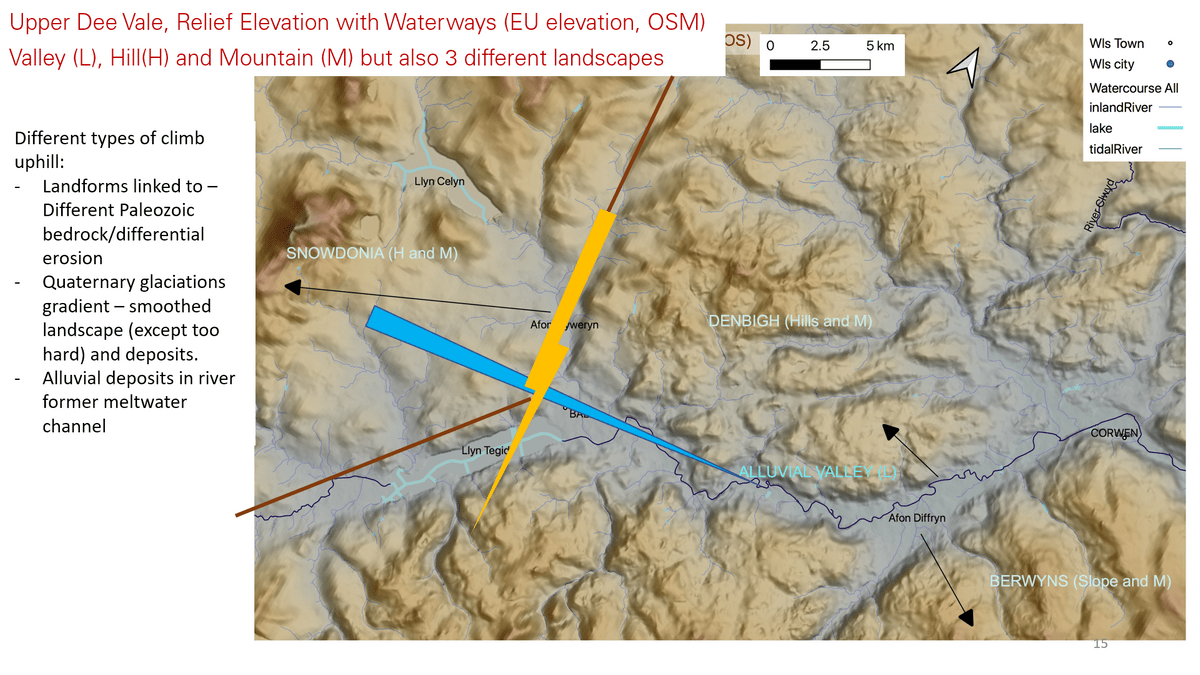

Landscape Analysis :

Different geology - Different glaciation impact - Stark vs Smooth landscape - Ploughable and non ploughable land

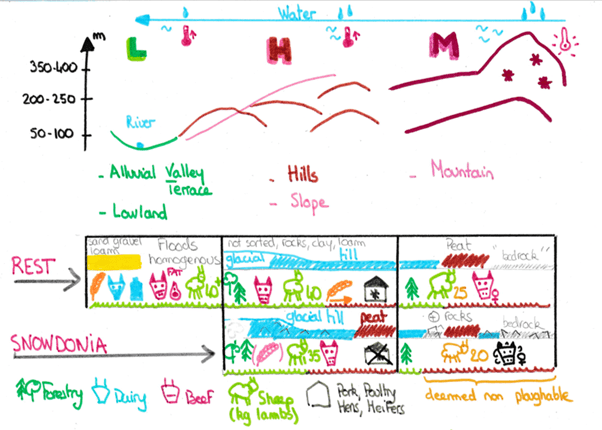

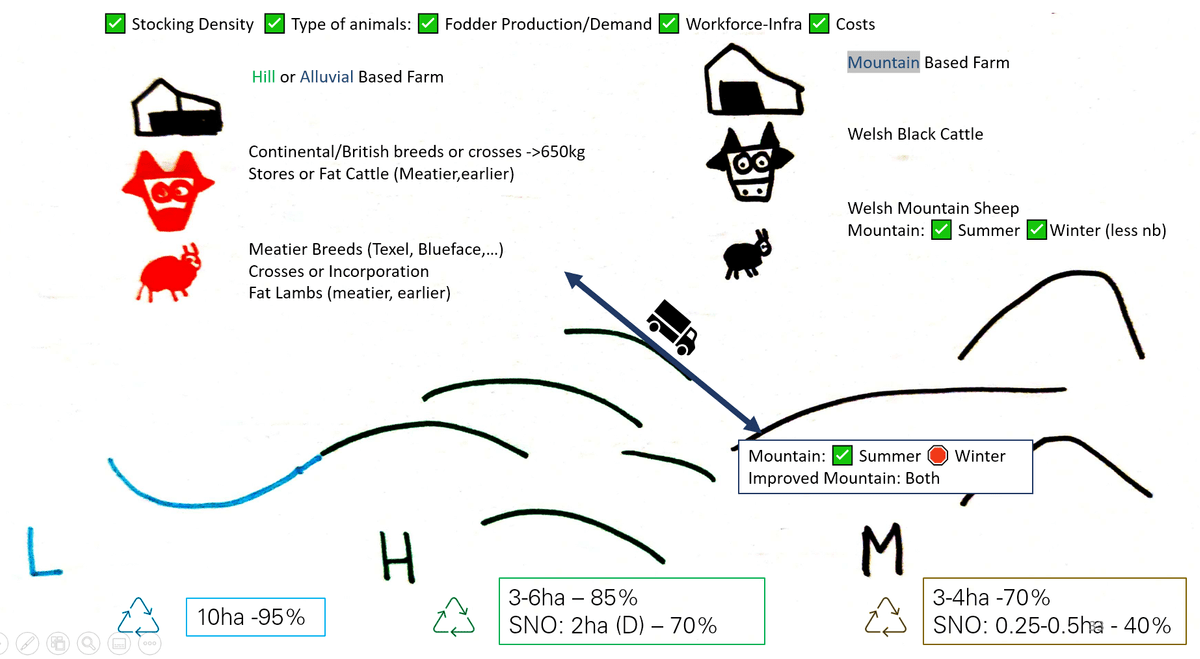

The lush wide alluvial valley transitioning to green hills (brown topped) or slopes to climb up to the more mountainous parts (higher in altitude and wide ridge arrangement). This general organisation from the Alluvial Lowland (L) to the Hills/Slope (H) and then the Mountain (M) can be found in every upland area.

The geology is the tool to understand the landform for Hills and Mountains. The heterogeneity of the rather soft and muddy substrate of the Denbigh Moor explains its hilly and contorted features compared to the plateau feature for the homogenous and hard rocks on the Berwyns.

Snowdonia’s side with more plutonic bedrocks offers a stark contrast, with outcrops pointing out to the sky in a bigger-hills landscape, with a greater inner heterogeneity. All these bedrocks result in acidic, clayish and loam soils. (Cf. Map in Appendix 1.)

The Devensian glaciation has smoothed landscape landforms and has resulted in massive deposits covering the study area. Snowdonia was the centre of this superficial surface glacier in North Wales. The poor quality tills (glacial superficial deposits) are overwhelming on H and M, only rocky slopes (sometimes scree) escape their cover. On the rest of the landscape (Berwyn and Denbigh Moor), deposits didn’t reach the top of the Hs and Ms. They are thicker on the flat parts. Peat deposits are linked to the glaciation deposits. These soils are not impossible to plough but are difficult to drain, plough, reseed – mechanize the window for those works is small.

Figure 1: Upper Dee Valley Catchment Dee landscape organisation, characteristics and potential agricultural productions/ Bio-climatic context and production types. (By the author)

The Dee Valley is the main watercourse for the catchment; dug out via glaciers melting and since then, it's floor is covered with good quality alluvial deposits.

The Snowdonia side of the territory is part of the National Park, while the other Ms are under environmental designations. The landscape is overwhelmingly green; what changes most between the different parts is the amount of ploughable land. This combined with a climate and soil gradient offers different farming conditions. The main crop is grass, it is gradually less palatable and has a shorter growing season as the altitude increases (long term temporary pasture).

(See Figure 1. below)

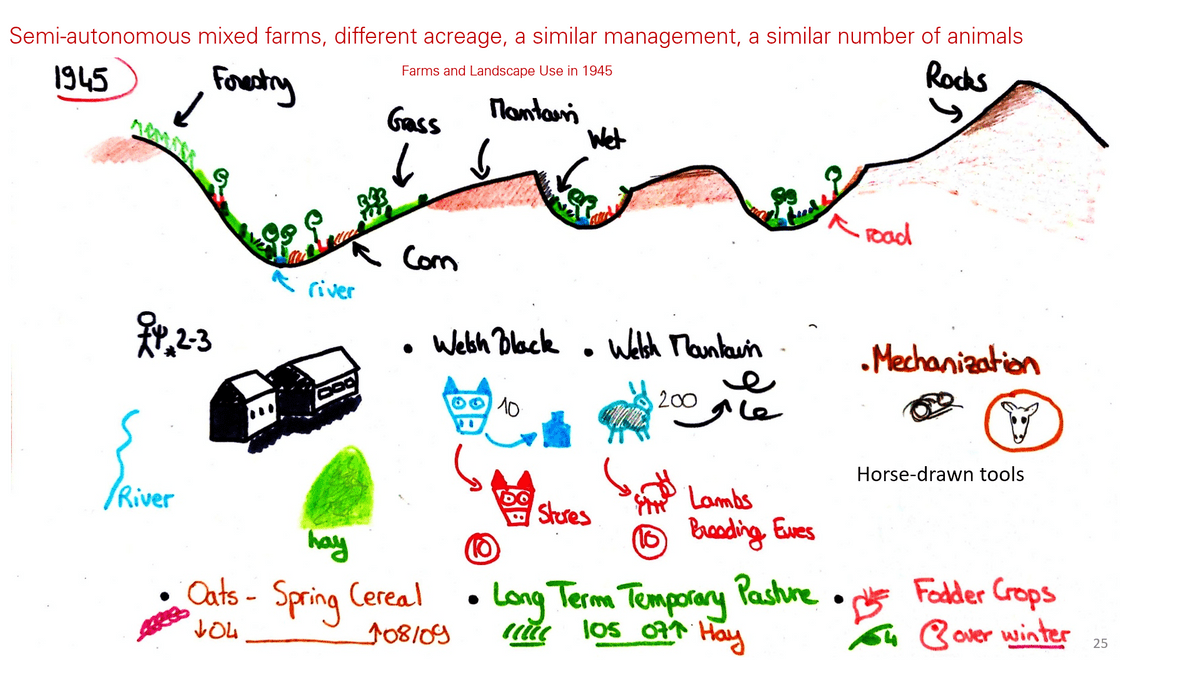

Farming History:

- fluctuating use of the landscape - Mixed farming

Bala is at the fringe of the “farmed area” in Wales, the diversity of agricultural potential makes farming in some parts of the landscape a daunting prospect (H and M). In the past the landscape was reclaimed in waves when the environment for farmers was supportive.

The Bala area was estate controlled, it had been enclosed, organised. It explains that when going up LHM (Denbigh/Berwyn/Snowdonia) the farms tend to control more land from the start to compensate the production potential imbalance. Likewise a scale of farm sizes were available for different social class farmers with different degrees of landscape control (a ‘Home farm’ will likely have all three HLM, “a strip”, whereas a smallholding will only have one of those areas).

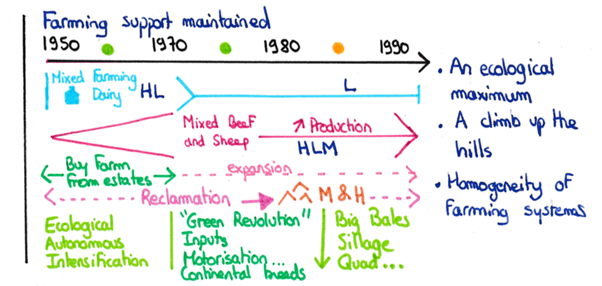

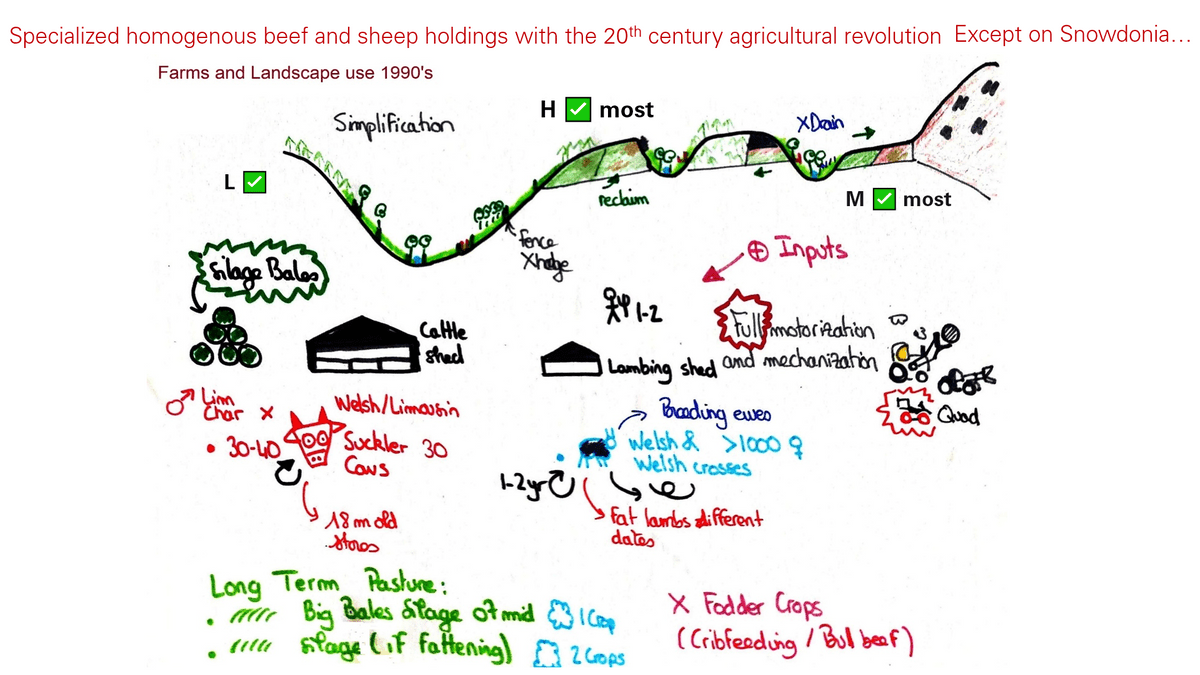

The post 2nd World War drive for food production profoundly changed farms from semi-autonomous mixed farms (dairy being their main output) to specialized homogenous beef and sheep holdings (couple dairy holdings had survived and increased mainly in the valley). This was the biggest tide of change the landscape ever knew. Bala’s area was included more intensively than ever into the UK food production network.

There has first been a drive for intensification of production (per available area) linked to autonomous, input-savvy systems and then moving to the input based green revolution as the policy changed. Continental breeds of cattle and meatier sheep breeds would be favoured over the low-maintenance, smaller Welsh Mountain Sheep and Welsh Black.

Farmers were secure in their investment on their holdings by the AHA or buying their land and were tremendously helped to increase their ploughable area (and days of use) on their farm (40%) to keep more animals. A real climb up towards the mountain with simplified farming systems relying on long lasting temporary pastures. A shift from brownish to vivid green, in the landscape.

Snowdonia is the real brown and black spot in a rosy picture. Its Hs and Ms require a lot more work to convert into ploughable area, the shallow/rocky soils or too deep a peat share is the bottom line. Any transformation goes slower and costs more.

1985 marked a real breakthrough for upland farmers with a massive productivity leap available for farmers (for work and production wise) with the Big bale silage (easier to deal with than the widespread use of hay before), the almighty quadbikes, and scanning and lambing inside. The access to the future of upland farming was then conditional on having capacity to invest. The tidal wave up the mountain stopped, as subsidies were reduced.

Finally it is worth mentioning that the road surfacing as well as combustion engines lorry’s, 4*4 had a big impact on the access to farms. 4 wheel-drive tractors also made easier managing the steep land or mountain work.

Note: Farms on Snowdonia mountain specialized early in sheep – Farming Commission impact with pine trees plantation

More recent farms history, economy and technical analysis. From an endogenous expansion to an exogenous expansion.

The subsequent analysis is the results of 60 farms’ history and technical/economy interviews. From this were deduced archetypes evolution through history and today's technical and economic operations.

During the last 30 years the intensification drive has been gently reversed. A new support environment combined with challenging food market conditions triggered farmers to adopt different options to safeguard their livelihood.

1990 marks the high farming age for Wales; Most farms were homogeneous (work productivity, tools…) with 1.5-2 people managing 30-40 Suckler Cows (to produce 12 to 18 stores) and 400-800 Ewes on very different sized farms. Farms with more mountain land would have a higher share of sheep and wouldn’t have applied all the new techniques linked to the green revolution. There were still a high number of workers in the area.

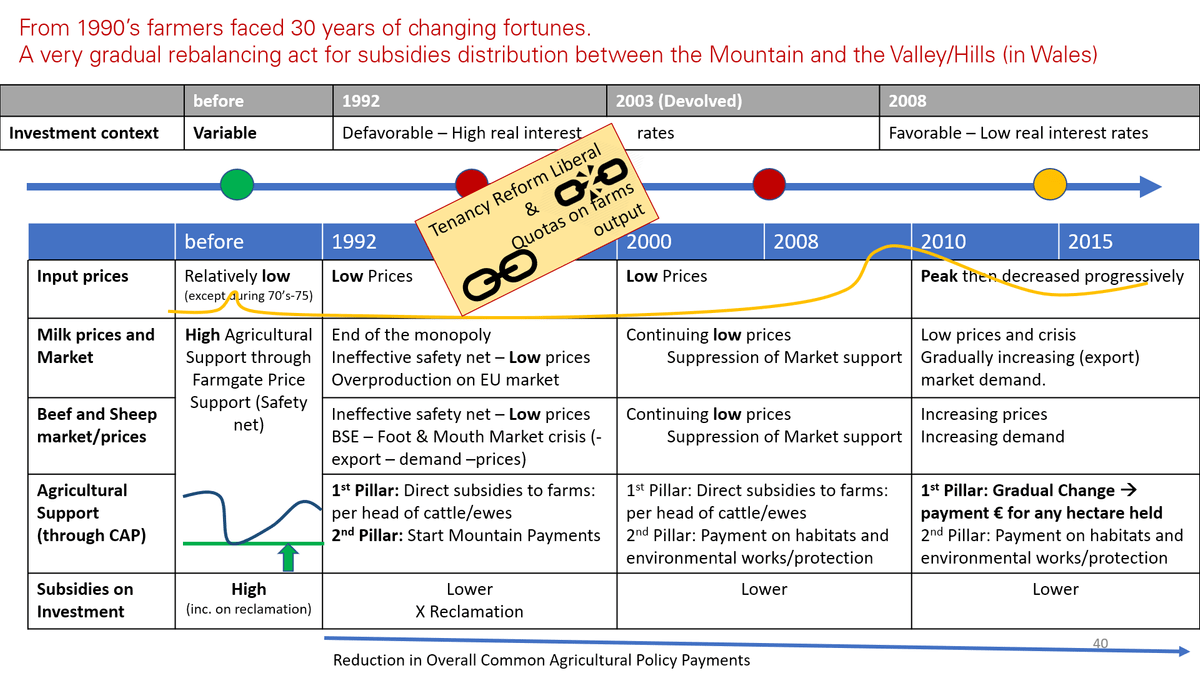

- In the 1990’s an input/output prices squeeze accompanied by headage subsidies and quotas. CAP support starts to move away from productivism

The balance of subsidy moved from favouring higher productivity (favouring H L) to favouring control over land and remarkable habitants/landscape (favouring M and Snowdonia). The first two decades favoured both farms able to increase their outputs and those with conservation habitats. With a selection in the valleys and hills on the age of the farmers (and number at home) and the type of land. While the last decade favoured farms with conservation habitats and big extent of lands. A selection directly on the amount of land held and its type as well as farm output profitability.

- Beef and Sheep: 80% of farms in the study area

The end of secured output prices and the move to quota- based subsidy payments triggered a focus on the numbers of animals. But this was mitigated by the first pilots for new agri-environments scheme. Combined with poor market conditions and BSE/Foot and Mouth crisis it created a pressure on Beef and Sheep farmers. It triggered smaller farmers nearing retirement to stop farming under this stressful and unprofitable time.

Quotas weren’t particularly limitating for beef and sheep farmers and the payments were very lucrative. The improved use of crossbred combined with an increase use of inputs most of all cake to get to a sooner and heavier market target.

To maintain their incomes, expanding was the solution for farmers outside of Snowdonia; in terms of animal numbers (and trying to build an income out of razor thin margin) or/and expanding the area controlled. Those doing it would be farms with a clear succession future and a minimum threshold size.

Some didn’t increase, some changed their size and equipment with minimum cost while others (on alluvial valley), some jumped up the scale and invested in a very difficult investment context requiring scale economies (land, sheds…).

The land market developed a lot under this pressure and its value increased; a wider need to make profit out of the land used to expand arose from this. It was remunerating for farmers/retirees to rent-out their land with the development of the new legislation (1995). Tourism was also an opportunity arising for some farmers. Allowing them to reduce their exposure to farming activities.

With the later regulations (NVZ 05) and wider scale AES the second was soon to be favoured. Farms that could afford it would try to stretch on L H M to maintain their output and respect Agri-environment commitments (and payments).

Note: end of dairying in 1992-1995 last farms in the valleys, bad milk prices combined with quotas and impossibility to justify new farming techniques cost.

- In the 2000’-2010’s a total switch away from production-based subsidies for farms; the development of agri-environmental subsidies: A development of opportunities out of farming.

Farmers that increased their production usually benefited from the 2005 Welsh CAP adaptation and maintained their system until 2013 when the link between production and subsidies was ditched. If no mountain land had been purchased these farmers were in a tight spot financially. Those farmers would tend to favour a more market focused product with an earlier lambing (partially indoor), bigger sires and crosses/mules thus with a heavy well conformed lamb sent rapidly to the market. Continental breeds of cattle with fat animals produced (bull beef…) or strong stores. The access to the L fields was the key to more of those gains profitably.

On the flipside those who gradually increased their grasp on more land and particularly mountain land (cheap because of poor production potential) were able to cash in huge gains.

Farm based on Snowdonia Mountain tend to be the ones with a high proportion of mountain land, are producing Welsh black (or crosses) stores and some Welsh Mountains lighter/later lambs that have a lesser value on the market. Didn’t have the opportunity to increase numbers much and were quickly incorporated in conservation/preservation schemes. With the new higher income thanks to subsidies they might have invested in Lowlands farms (Denbigh, Corwen, L) in order to have more grass available.

The Agri-Environment payments accessible on mountain are/were 10 times better than possibly attainable in H or L given the sheer amount of high value habitat held. A jump in subsidy per acre not matching the many constraints linked to lower Agri-Environment payments in H or L.

Farmer’s that went organic (triggered partly by transition and maintenance grants) had a wide access to land to allow them to multiply per 3 their farmed area (H and L) but low-pressure farming in mountain also had an easier switch. They had never been able to fully benefit from the green revolution. It was also an easy step for estate home farms with large amount of land that could be farmed back in house. Having access to the L part of the landscape meant being able to diversify into more production intensive crops.

- Other non-farming ventures

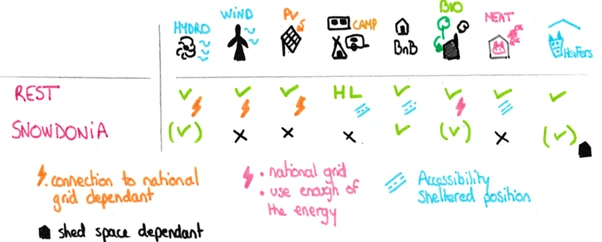

Figure 2: Other ventures than Beef and Sheep are firmly linked to the position of the farm in the landscape and are highly discriminatory without mentioning the capital cost.

The 1990s marked the diversification of farming systems into campsites or caravan parks for tourism thanks to the link with Snowdonia. Those are found mostly down in the L or H. Over (very profitable) opportunities were offered in the energy production sector. These capital investment are costly, location specific and require you to have full control of the land. This sometimes meant downsizing the farm to cope or having extra labour on the farm.

Nota: Here we use the word diversifications, adding non-farming activity as a side economic activity to the farm. It is different from the differentiation (that encompasses the diversification) whereby farm choose different paths/mix of activities depending on their opportunities, possibilities (bio-climatic, workers qualifications/abilities...).

- Poultry and Pork sheds:

Sustained demand for free-range eggs since the turn of the new century (increased consumption) has meant that profitable contracts have been offered to farmers. These options require a sizeable capital investment, NVZ compliance and planning permission.

All those options are rather profitable some due to government subsidies and others sheer market demand, but these 3 criteria select those who can go for it.

CAPITAL - BIO-CLIMATIC POTENTIAL/LOCATION - MARKET

- The dairy sector development is impacting Upland Wales

Sustained demand for milk since 2010 in the British dairy industry and a renewed focus on grass-based milk production has enlarged the scope of potential areas for dairy holdings. The alluvial valley offers mild conditions, good soils and suitable grass growth calendar. The lesser grass growth than in lowlands is compensated by the area of the available grazing. This opportunity is mainly linked to estates’ home farms that can pull together a sufficient scale of land area from farms taken back in hand. These are spring calving low yielding dairy farms with a focus on cost reduction.

Finally, the development of the dairy industry and the growth of most holdings has meant that the ones most stretched either for staff or land can operate as flying herds. Uplands H or L are appropriate territories for heifers to be reared on grass, roots or sometimes inside. This offers good and regular returns for a (relatively) small and gradual investment.

Economic performance of Bala’s farming system archetypes:

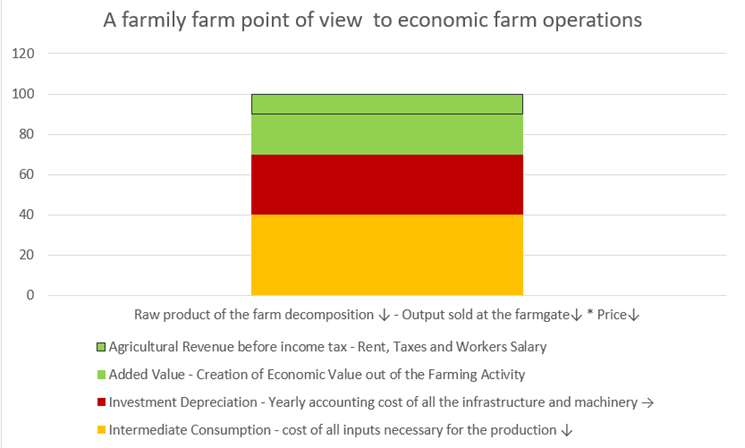

The economic results we computed for every archetype farm system shows the diversity of Bala’s farms even when focused on the same production, but with very different results due to the landscapes in which they are located and their historic differentiation.

RP: Raw Product IC: Intermediary Consumption DK: Capital Depreciation AV: Added Value LWG: live weight gain

All prices in € 2018

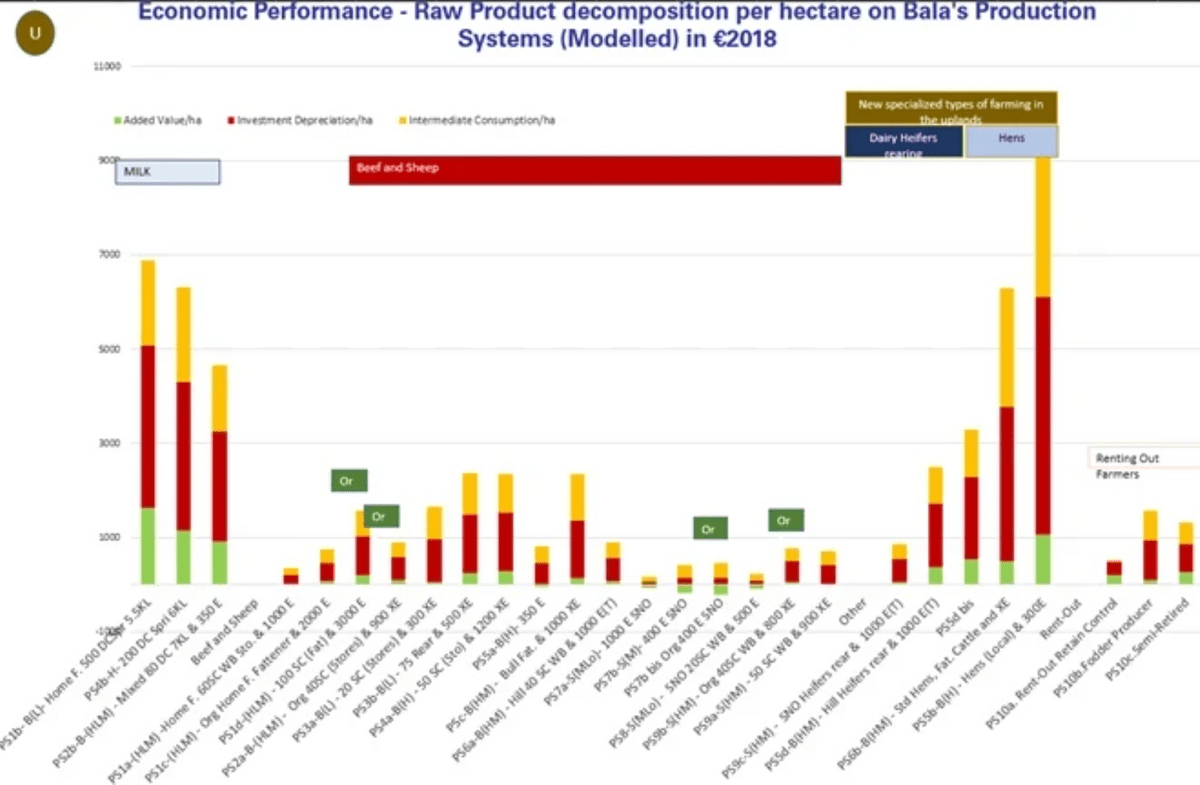

- Raw product per hectare per archetype:

We have a huge gap in terms of raw product per hectare mainly linked to the intensity in terms of fodder production per landscape farms have access to in the study area. Farmers that own some mountain land have a lot lower acreage output. We can also notice the fact that very few farming system create some economic value, and some destroy some economic value. Only farms not depending on the land to produce or having only access to higher quality land access higher added value per hectare. Overall added value and raw products per hectare are way lower than in Pembrokeshire and can be linked with the lower land productivity potential.

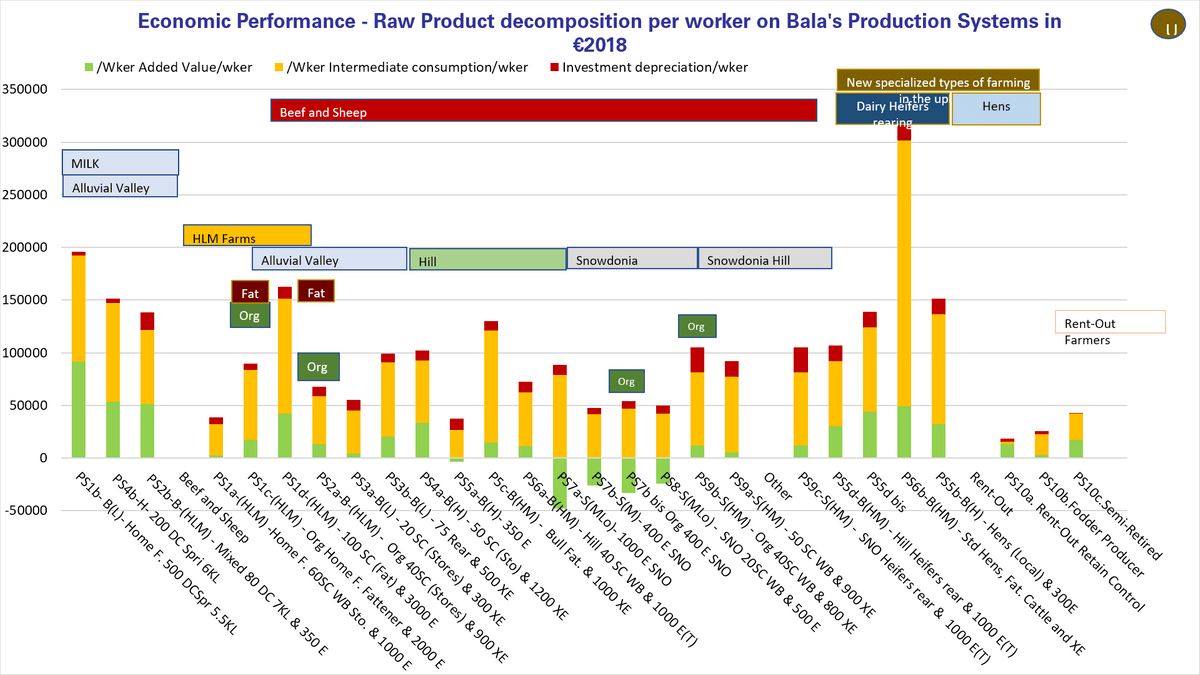

- Raw product per worker – looking for the work productivity of farming systems:

Overall the added value produced by each system is really low for all beef and sheep system, at the same level as in Pembrokeshire while farmers cater for more for livestock (cattle herd is roughly the same but sheep number are higher). We notice that the Raw Product/Worker is more balanced than the RP/ha showing us that most farms have the same work productivity. Most mountainous farms on Snowdonia have a negative added value sometimes going as far as -48000€ 2018/Worker. The Intermediate consumption are higher per worker than in Pembrokeshire and the capital depreciations seem similar. This could be linked to higher input linked with the additional sheep and the longer winters. Even though liveweight gains tend to be lower than those achievable by farms in Pembrokeshire.

Those that stand out of the crowd are the dairy farming systems, finishers and organic finishers as well as the newly specialized farming systems. The high valued in-demand outputs leave them a higher added value when taking into account relatively low cost and capital depreciations. This except for the landless hens farming systems that have high inputs cost because they buy in the feed for their hens. Dairy farms only using the best of Bala’s land easily reach the highest added value/worker of the area. We can clearly see different strategies in terms of input use vs output sold between farms.

The smallest farms (<50-60ha) also tend not to return any added value or have negative ones with a lower amount of work provided from their sometimes-part-time farmers.

The PS1a legacy home farm tends to have a low worker productivity due to the number of hands working on the farm compared to what is needed (with 2 family workers, the owners less involved or having to deal with other activities).

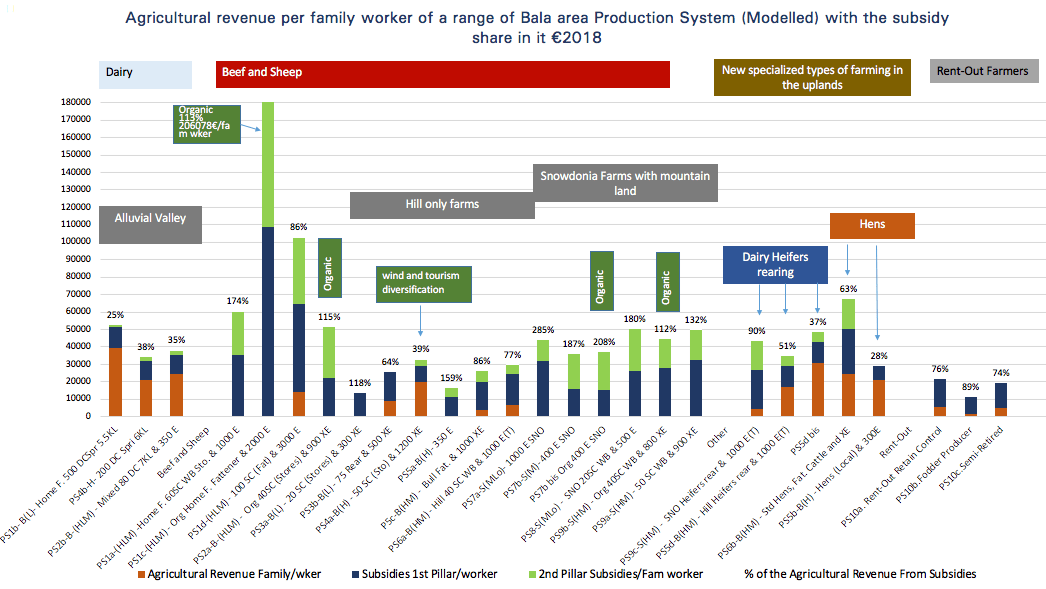

- Looking at the Agricultural Revenue per family worker on the farm:

Comparing it with Pembrokeshire's farms income and where the income comes from is very interesting. In Bala contrary to Pembrokeshire the majority of the archetypes see their income depending entirely on the CAP scheme and most of those farms have 2nd Pillar payments compared to very few in Pembrokeshire. The dairy farms income doesn’t depend much of subsidies in both areas, they high acreage production and added value is crushing down the subsidy share in their income (and their high workforce as well). On the flipside Beef and Sheep farms on the hills and on the valley can very much be likened to the Pembrokeshire ones in terms of income amount and constitution. They are the ones with the lowest level of income overall in the landscape and that don’t reach the renewal threshold of 30-35 K€2018/year.

The higher income per worker displayed by farms in Bala area on beef and sheep system compared to Pembrokeshire can be linked to the fact that farmers cater for a higher number of animals (sheep) and most of all to the increased amount of land help by Upland farms and particularly mountainous farms.

PS4a is showing us the effect that diversifying into energy production can have on your farm income, it takes away the dependence on subsidies for a dependence on the electricity rate.

Some farms that returned high added value per worker depend entirely on subsidies for their income because of the weight of paid labour, that’s the case of the three home farms whatever their strategy. But thanks to their huge amount of land held they reach very high incomes per family worker thanks to subsidies.

Farmers that are on the hills or have mountain land and don’t have the opportunity to access the new specialized type of farming with rearing dairy heifers and free-range hens, those offer a lesser dependence on subsidies and a higher income compared to the other beef and sheep farms with low amount (or no amount) of mountain land.

Finally Rent-Out farmers, farmers that have at least partially retired and maintain their hold on their owned land, can access a relatively interesting income sometimes higher than if farming their land completely. Those farmers tend to have access to other incomes sources.

Overall the 2013 redistribution of subsidies benefited farms that hold most land and not necessarily those having the highest number of workers. It certainly contributed to a reduced intensification (in terms of land grazing intensity/fodder production) without the incentive to produce more. It allowed the farms that lose money out of their farming activity (negative added value) to stay in the landscape and maintain some of the “traditional welsh family upland farms”. Those mountainous are the ones having less options to evolve into different farming systems. But now it also tends to fuel a higher concentration of land and farming by having a x15 spread (difference between max and min) on income per family worker in Bala area and a x19 spread in terms of subsidy amount per worker.

In Pembrokeshire the spread in terms of income is only x10 but the subsidy multiplier is the same as in Bala. Though the Min is only 13K€2018/ familyworker and the max is 26K€2018/ familyworker compared to 8039€2018/worker and 152K€2018/familyworker max. Besides in Bala highest income per family worker archetypes are linked (except for 2 systems) to farms with with over 100% of subsidies (when looking over 90000€2018/year) contrary to Pembrokeshire.

Nota woodlands: are not included in farmlands. Estates own some woodlands and so are other institutions (NRW, crown…). They might own only 10-40 acres. Most woodlands are located in areas that would be hard to turn into pasture with sustained potential. Rocky or steep slopes, rocky hill tops… Farmers have been planting some patches whenever they are not too tight and are willing to do so on their poorer land.

Conclusion:

Finally, it is important to note that Upland farmers are more and more just herdsmen, the use of contractors is widespread for most other farming operations. Contracting offers an important share of work for the younger generation in the farming community. The concentration of holdings and land has continued at an alarming place, driven by income needs.

The reliance on subsidies is hugely different between farms and is directly linked to who controls the land and, now, the mountain. The unprofitability of many farms is not so much linked to a reliance on inputs (compared to lowland farms, these farmers are extremely savvy), but to the low market value of outputs. This has been one of the main drivers of the concentration of farms. Also, commodities – which is what most hill farms are producing/selling - are much more vulnerable to agricultural price crisis.

Farmers plan their farming system on a lifelong basis. For individuals, capital investments are a heavy burden and sometimes unattainable. For several options, enabling farmers to achieve higher added value depends upon being able to invest - this discriminates strongly between those who can, and those who can’t, and it only allows farmers that have built the right business structure to develop capital, to go ahead.

Before going any further in thinking about agricultural policy have a look at how payments are distributed between farms in your local area or in Bala area (LL21 or LL23) on this open data website:

CCRI Winter School

I presented my work on Bala area at the CCRI (Countryside and Community Research Institute) winter school on the 21st of January 2021. You will find below the slide of this presentation and later on the video.

Questions and remarks on the presentation:

Speaker A: Would be good to hear your thoughts on the future of agriculture 4.0 in upland systems!

Agriculture 4.0 definition is well summarised in the abstract of the DC Rose 2020, frontier paper: "Agriculture is undergoing a new technology revolution supported by policy-makers around the world. While smart technologies, such as Artificial Intelligence, robotics, and the Internet of Things, could play an important role in achieving enhanced productivity and greater eco-efficiency." https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2018.00087

Each agricultural revolution came with incredible jumps in terms of work productivity or food production potentials. In the UK agriculture revolution that took place in the last 200 years have lead to a mass reduction in terms of workforce employed. For example it is quite clear that the fuel powered 20th century agricultural revolution lead to mass work productivity increases that allowed people to cope with 4 times more animal with a workforce divided by 2 to 4.

In a context were for the last 30 years agricultural produces farmgate prices have been particularly depressed farmers trying to maintain their income had to increase the size of the farm (for an income mainly composed of subsidies in the upland).

If the Welsh nation is keen to preserve the socio-cultural fabric in rural areas, it also means that an already vastly reduced farming community needs to be preserved (Welsh language, culture, traditional land management…). If this goal is to be fulfilled there is only one way to introduce agriculture 4.0, respecting WG commitments to environment while avoiding a new haemorrhage in the community.

It means using the agriculture 4.0 to chase revenue and cut costs while releasing time for farmers to deal with their agri-environmental commitments. The future Agri-Environmental Schemes having to play a second salary part as environment (in the broad term) squires. Let's face it GPS guided tractors are of little use in the bumpy uplands and no farmers on the hill or the mountain would be able to face the cost of this machine. On the flipside drones to check on sheep, scales to know weight/fat levels could be handier, cameras to monitor calving. But it is also important to use the 4.0 ag revolution to serve the goal of Agri-Environment Schemes for example: NFC eartags to keep track of cattle/sheep movements, tools to help lay hedges.

But it won't be the only solution to the output price squeeze that farmers are likely to continue to face in the coming years. The race towards greater output to whether lower margins is not sustainable for the community and for the environment (even if uplands farms are very input saavy). As farm grow bigger it is more demanding (even with upgraded/4.0 tools to keep track of things). 4.0 ag revolution needs to be about a closer focus not a bigger focus.

Economic sustainability is really important but also important to acknowledge upland areas as being key with regard to the sustainability of the Welsh language, culture and heritage

Speaker B: You've looked at a historical context - where do you see things in 50 years time in the Bala landscape?

It is quite striking to witness the amount of transformation that happened in the last 30 years. There are many routes that can be followed for the years to come. But as time evolves I think there will be a further differentiation happening in the future.

We are at a pivotal point, opinions within our society differentiate firmly on how they want to source food and what they are expecting from it. Meaning there will still be a commodity world market, one world, one price for a range of standardized (homogenous - thus a quality in itself) produces, those markets will still feature fluctuating prices. On the flipside it is likely that niche markets will gain momentum gradually. Either on local foods, certifications (organic, welfare…) offering a more stable market but on reduced volumes also featuring a lower work productivity. This second option fitting well with the very tourism/leisure focused industry of part of Wales.

As per the future Welsh Agricultural Policy it is quite clear that farmers will have to try to get to a double sustainability (economic and environmental) I feel that farmers will continue to differentiate adapting to those two sources. This might mean the development of new specialised types of farming on productions were Welsh landscapes are not sustaining the demand yet including horticultural; vegetables or fruits productions (including some alcohol production). Or even by developing transformation of agricultural products where those facilities don't exist in Wales yet.

On meat and dairy Welsh farms could develop those local scheme but this would be more challenging given the scale of existing farms and their degree of specialisation.

I don't think that there will be a major price evolution on farm-gate products allowing farms to consider a massively increased economic sustainability following other paths and without subsidies.

We also have a climate emergency in hand combined to a forecasted end of fossil fuels at some points during the 21st century. Farms will be challenged on this side and will have to whether increased climate variability constantly adapting their farm's management. Combined to the future WAP I think there will be first vast reduction in input use (though some localized part going on high added value productions might witness the contrary) and some ecological intensifications on some parts of the landscape (to be able to maintain some production without input all the more if the farm area is reduced see below). A development of the wooded area is likely if the right incentives for trees planting are put up (mostly lasting) as well as on the hedges. A better use of livestock muck will be certainly sought every subproduct having to be used efficiently.

Overall a differential use of the landscape with bigger gaps than it is the case today is likely in the future with wildly different fodder productions per acre and work productivity depending on where you sit in the landscape and what route you followed. It is likely that the regulations will lock down farmers from backtracking - thus it could deter farmers (particularly if support levels are not sufficient).

Speaker C: Alongside looking at the topography of the land, have you looked at other geographical characteristics which affect their practices, e.g., soil type, drainage?

From the geology comes the relief - from the deposits or the bedrock rises the soils. Due to the diversity in deposits thickness, types (or absence) there are very different soils types and drainage quality across the study area. I've put it more in the summary and the full report

Most soils in the study area would be classified as clay or loam. Some would be also be classified as peaty.

The difficulty in explaining the landscape is always to frame it into the most palatable and accurate summary possible. Both Bala and Pembrokeshire are good example of the landscape analysis taken amalgamating the many sciences impacting farming.