In 2019 I had the opportunity to do an agrarian diagnosis in a small agricultural area of South Wales. We choose to study South-Pembrokeshire, this was part of my Master's Degree thesis, the thesis was sponsored by the Carasso foundation and co-tutored by AgroParisTech (Fr) and the CCRI (UK).

South Pembrokeshire is located at the south-western tip of Wales: it is a coastal lowland representative of South Wales. This scenic area is well known for its diversity of coastal landscapes and red soils. The study area covers a diversity of bedrock and a gradient of oceanic influence on its crescent-shape from Narberth to Castlemartin.

Pembrokeshire a hilly bocage area with a North-South soil and climate gradient, typical of South Wales lowlands :

South Pembrokeshire (Pbs) is a hilly lowland area under 200m of altitude with a bocage landscape (a landscape with fields delimited by tree lined hedges and lots of grasslands). Away from the coast, South Pembrokeshire has a landscape which can seem very homogenous but in fact offers a variety of potential depending on the valley size and steepness of slopes which can be linked to different bedrocks. This diversity allows for a range of typical welsh lowland agricultural production to take place in Pembrokeshire including; milk, beef, sheep and potatoes. Pbs farming is very much focused on livestock and grassland.

The geology of Pbs helps us to understand and divide it into 2 big valleys/hill types with contrasting agricultural potential, which must be combined with the climate gradient. On cold mudstone with coal seams, valleys are smaller and gave rise to loamy, clayish, very heavy soils. They are not as free-draining as other loamy soils in Pbs. The other substrates give bigger, smooth valleys and hills due to their increased permeability. The soils they give rise to tend to be more free-draining. Overall superficial deposits are scarce, mainly good and alluvial (sand, gravel and loam) around the watercourse. The relief differences that can be seen on the figure are due to a differential erosion process.

Drier, more free-draining soils are easier to crop (to turn into early potatoes) or to use with farming machinery, they will also feature earlier grass growth and could be harvested more easily.

On big ridges; the landscape is overwhelmingly green with most fields being temporary grassland linked to beef and dairy farming systems. Overall the management of pastures is varied; there are some mob grazed every 2 months, some temporary grassland is intensively grazed every 12h or cut for silage 3,4 or 5 times per season. There is a high production potential and the management can be extremely different, as is the production of grasslands. There are Some Maize and wheat/cereal fields for fodder but potato fields are the only commercial crop around, they can be found nearer to the coast on Old Red Sandstone and Limestone geological substrates. On small ridges; fields don’t offer this range of potential harvest and crops because of their limitations, thus the top limit is lower. No potatoes, scarcely any maize or cereals.

The production of those pastures is still way above what upland pasture can return, due to the milder climate (extended growing season, better growing conditions…).

Pembrokeshire farming history

This work is the result of 6 months’ fieldwork in South Pembrokeshire where I in-depth interviewed 90 farms on their history and today’s farming systems.

Abreviations: EU: European Union/EEC UK: United Kingdom WTO: World Trade Organization CAP: Common Agricultural Policy (EU) Pbs: Pembrokeshire

- From subsistence farming to market integration, the beginning of the 20th century Organized estates/ Diversified mixed farms relying on diverse productions. Well connected to other parts of Wales.

In contrast to several Wales’ upland areas, Pembrokeshire was always accessible (by sea, then rail, then road…) quite rapidly. Soil quality potential offers a diverse range of outputs and production. The landscape in its differences remains relatively heterogenous? compared to an upland area and with a much higher production by acre.

Pbs (as was most of Welsh lowlands) was cleared and farmed early on. It was one of the first areas to be taken by the Normans in Wales; the feudal system was thoroughly implemented (by church, aristocracy, squires) and later evolved into estates. Landowners triggered the reorganization and amalgamation of farms in the 19th century which was to adapt to changing market conditions (in favour of livestock products), adopting “ley farming” with the enclosures. Farms could be divided into 2 categories; small autonomous family farms and bigger holdings destined to sustain a commercial output. All farms were mixed and had some sheep, beef and dairy cattle as well as a variety of crops. In Pbs grass leys with clover were rightly seen as a terrific use of the land available. Obviously it was more work on smaller, wetter ridges with their heavier soils.

The death duty gradually rose in the early 20th century and marked the first move towards independence for profitable Pbs farms: gradually paying back the loan on their farm by selling surplus. This was done at a terrible time for farming; the 20s depression. But Pbs’ focus on grass-based systems was allowing farms with a quite high work productivity to keep selling perishable goods, as well as wool. The closer to the town, city and railway, the better the price paid. The demand from industrial towns was rising.

Wikimedia: Haymaking in Dyfed. Mechanization was already well advanced in the 1920's compared to the uplands.

The 1930s marked a change of fortune with the creation of the MMB (Milk Marketing Board) a union wide monopoly on milk collection. Its creation triggered a wholescale rationalization of milk collection with one price offered for all and a drive for sanitary improvements (TB). This gained traction among grass-focused Pbs farms who were sure to be able to sell their surplus. At that time a leap in production and productivity of farms appeared, combining milking machines, the hay shed, intensive work – fodder production in heavy rotation (for all the year), and using the shorthorn/british freisian breed. No more transformation of farms outputs meant the workforce was able to keep more cows. There was a gradual uptake linked to past good or bad fortunes (time to buy farm vs interest rates, already close to the railway, selling directly…).

The 2nd World War (WW2) marked an optimum of ‘ecological intensification’ of production with very diverse rotations (Norfolk rotations with potatoes on big ridges), combined with intense work. But it was a relatively prosperous time and post-WW2, starved Britain kept supporting family farming to reduce its reliance on imports. Policies secured farmers’ tenure and stabilized output prices…

Farmers on small ridges would start to take the leap in endogenous production while big ridges farms were starting to get toward mechanisation and an increased use of inputs (fertilizer (for potatoes mostly) and bought-in feed).

Nota: In Pbs farms were quite diverse and could top up their income by rearing Christmas poultry, producing weaners from sows (intensive work, bought-in feed). If enough land was available a beef or strong store (24m old) production would also be present. Farmers on the big ridges could access the cash crop; early potatoes (intensive work, better on warm, free-draining red soils).

- A wholescale, monolithic , endogenous dairy specialization in Pembrokeshire based on grass

In the 1960’s came a new revolution in dairy farming for this favourable grass growing area. Wet parts of the landscape, including the small ridges could easily benefit from it. It was a combination of high-yielding Rye-Grass, fertilizer, rotational grazing, improved British Freisians, silage techniques (wet harvested) in a simplified grass rotation, a new parlour/tank to cater for more milk. Silage (and drum mower…) was a revolution for wet Wales, more cuts of grass could be made regardless of the changing weather.

Geoff 1969, National Library of Wales. A revolution hit in terms of work productivity all dairy farms in Pembrokeshire with an endogenous dairy expansion. British freisian cows in a 6 abreast milking parlour.

By 1970 the focus for Britain had switched from feeding itself to exporting food. The continuous support for “improvement” investment (sheds, drainage..) was matched by a favourable yet risky context financially. The adoption of this leap was self-supported for most farms but some smaller holdings 20-30a started to retire (cottagers), this lasted until the 1980’s when milk began to be in oversupply on the EU market and export markets were not sustained. A rather homogeneous landscape and farming system arose from this period.

The movement described meant a specialization away from mixed farming into grass-based dairying. All the resources on the farm turned towards milk production with work productivity gain driven by mechanization. Farms gradually dropped their sideline production: sheep were the first to go.

- Farms not able to adopt these moves were gradually phased out of the market because of a more challenging input/ouput price relation.

Geoff 1959, National Library of Wales. Potatoes harvest. Early potatoes was the cash crop of Pembrokeshire that fuelled up a number of farms on big ridges in Pembrokeshire.

The only farms not specializing in dairying would be those with ample supplies of red soil on big ridges. They could grow early potatoes as well as feed wheat. This could be used for fattening beef cattle rapidly with the use of more demanding continental breeds. Potato farming gradually fell into decline due to price pressure (volatile prices and an expensive crop). Those farms were less rapid to switch from dry hay to wet silage.

- Changing times: The 1990s a turning point for the implosion of Pbs dairy industry with hyper-specialization of dairy farms in challenging times.

In 1984 to curb the growing milk oversupply and control CAP spending, the EU and UK changed tack and introduced quotas. The latter would also be the main driver of the 1992 reform (along with WTO compliance). It put a lid on the entire UK dairy industry that would later implode into the 1990s. Slower dairy farm expansion and a development of bull-beef rearing units were features of this change.

In this context farmers took different routes depending their profile, mostly depending on their position in the landscape, their age and the number of family members on the farm (i.e. how many farmers would share the potential income of the farm). This was a ruthless selection process.

Farmers close to retirement and no immediate succession went out of dairying (sometimes helped by schemes). Depending on their holding, farmers went into beef to reuse their existing layout, fattening more on the big ridges, producing stores on the small ridges. All associated with a sharp decrease in production, but still mainly grass-based.

Dairies preferred to collect from fewer, big farms and offered them higher prices. It was nevertheless challenging to expand in this context, production heavy strategies were thus favoured to make the most of every inch of ground rented/quota paid/investments and still have a disposable income.

In the mid- 1990s Puffin Produce cooperative was created by subsisting potato farmers, reducing the market oligopoly and targeting rewarding markets (chippers, supermarkets..), it gained ground. Farmers on red soil, able to irrigate and spend/loan the upfront necessary to pay for the kits were relatively few (not to mention the coop buy-in, cold stores...). The potato rotation spreading over 5 years led these farmers to rent-in consequent amount of land (Seasonal) without having to farm only their land. An input-heavy but high output operation.

21st Century Evolutions: More concentration and specialization of farms

The turn of the century was marked by the eve of hyper-specialization. A gentle easing of investment conditions combined with much reduced quota prices offered new opportunities to expand more easily. Milk prices were still depressed and the output/input price relation was not evolving well (oil prices increased, soybean price increased…). To make an income out of ever thinner margins every dairy farm had to try to expand.

Dairy firms offered differential prices not only for farm sizes but for the milk production pattern and milk quality matching their processing needs. For example, to flatten out the spring flush peak, a premium is offered for autumn milk (higher for autumn calvers that have their production peak in winter) and a penalty for spring calvers.

Farms that expanded during the 90s were already stretched thin as well and had no other choice but to keep pushing up numbers and milk production, taking up the IT revolution to increase their work productivity (GPS automatic driving, rotolactor, mixing machine..). With more investments they wereextending their grasp over more and more land further away from their homestead. As herds grew (and acreage available) and yield grew (not enough nutritional quality in grass) it became more and more difficult to include grazing in the cows’ routines and some farms went all inside. Herds exceeded 500 cows with milk yield over 9KL/year/cow.

The IT revolution also offered some work productivity tools (robot farming) adapted to smaller farms of under 200 dairy cows.

At the time the whole crop – wet harvest for wheat (quite suited to Pembrokeshire and Wales’s pedo-climatic condition) offered a new high energy crop suited to every part of the landscape. This was also combined with a grassland revival. Most farms had moved away from short rotational grazing as herds grew and the grazing pattern wasn’t linked to an efficient use of the grass growing cycle.

Since 2005 Organic farming started to pick up pace, linked to new subsidies during and after the transition. Combined with big ridges, this allowed good yields thanks to a diversity of crops in the rotation.

In 2008-2010 and 2016 two crises affected the milk market shaking off farmers who were not competitive enough, and pushing the others to maintain margins. But since 2016 the milk market has been supportive in the EU as a whole, and there has been more demand from the UK processing sector (controlled mostly by EU firms Arla and Muller-Wiseman) to increase milk production.

Since 2008 we have also witnessed very good interest rates and an appetite for safe investments, even if they are low yielding. This includes numerous dairy business ventures, particularly as spring calvers. The main size element for the number of dairy cows on every farm would be the size of the grazing area and its production potential.

- A number of low input, low output systems have developed most of them grass-based (or using a diversity of crops, for organic). On small ridges it would be a smaller format. Cow numbers could range from 90DC to 120 DC for “legacy” family farms and up to 500DC for spring calvers.

- The middle category might crop some wholecrop to add up to the bought-in feed to reach 7.5-8Kl/Cow/year with 200-250DC.

- Some High Input High Output dairy systems with high yielding cows and energy heavy crops, who took up the IT revolution. Number of cows can be in 100-150DC range (1-2 worker) or 500-1000+.

Among farmers dropping out of dairying, a range of store producers and fatteners is still very much present. Among new trends in beef is calf rearing (from dairy farms) for fattening or sale as stores. The wholecrop cereal silage offered a new opportunity for small ridges farmers to go into fattening. As the beef market gently recovered in the 2010s more farmers tried to go into fattening using ?corn? or wholecrop. There is a real range of No input Low Output vs Higher input Higher Output in beef and sheep units, depending mainly on the age of farmers and their access to land.

After retiring, a number of farmers are renting-out their land while still maintaining their farmer’s status. Some support farmers growing crops and rearing heifers for bigger dairy farms have also appeared, out of former dairy farms. A couple of sheep farmers are also present in the landscape.

In Pembrokeshire today most farms are still grass focused but under the cover of an overwhelmingly green landscape (over 90-95% and closer to 97% in winter), there is more diversity among farms and between farming systems than ever before. Pbs farms are working as an ecosystem trading goods to make a profit out of this good quality land.

Young farmers, newcomers to the industry tend to join as Dairy Farm Spring Calvers (FBT business ventures) or small part-time Beef and Sheep holdings with the ambition to increase. In Pbs the rent prices have been driven up by expanding farms.

Pembrokeshire Farms Economics

The economic results we computed for every archetype farm system shows the diversity of Pbs farms even when focused on the same production, but with very different results due to the landscapes in which they are located.

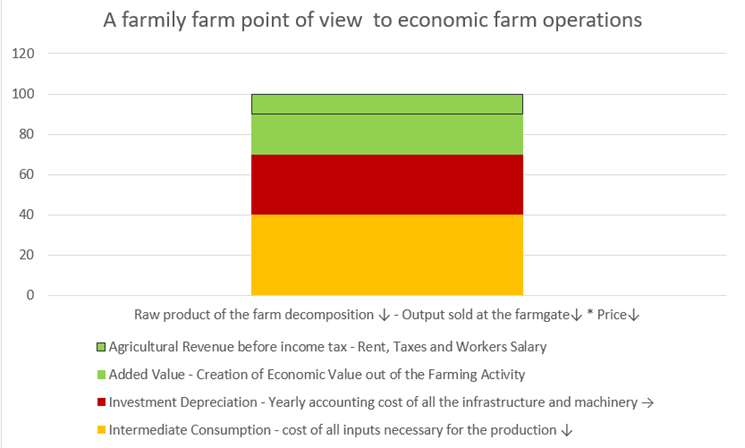

RP: Raw Product IC: Intermediary Consumption DK: Capital Depreciation AV: Added Value LWG: live weight gain

All prices in € 2018

- Added Value and gross Product for farm in Pbs, few productions are rewarding:

Dairy systems and potato farms are the ones with the highest gross production amount per hectare thanks to a high output out of the land. Intermediary consumption is way higher in dairy systems than beef systems, the lowest ones will be found with heavily grass-reliant systems.

Pbs farming systems rely very heavily on IC (Intermediate Consumption) (60 to 70% of RP (Raw Product)) this is due to the low amount of farm tools they reflected in low DK (10 to 20% of RP) (Capital Depreciation)). Added value (AV) in the production system is linked to a balance between the amount of money you can get for your output and how much inputs you use in your production process.

Beef system have a lower AV (added value) per ha and per worker than dairy systems, some beef and sheep farms have a negative AV, they tend to produce either stores or have a low number of animals and are typical of pre-retirement systems.

Systems that have very high AV/ha are the ones who invested in expensive farm equipment at some point (Wagon mixer, rotary parlour, robots or new potato kit) to reach an ever higher work productivity either on beef, dairy or crops. All AV/ha go over 200€/ha on dairy systems and 100€/ha on beef, and can reach over 1500€/ha for potatoes and dairy.

Some farmers choose to try to produce highly valuable goods to get a good AV, like 30 month slow-reared beef or autumn milk, potatoes or organic produce. Beef producers that fatten animals get twice as much AV/ha than the ones producing stores.

- An enormous spread in terms of Agricultural Revenue, small farms depend heavily on subsidies:

The average agricultural revenue per family worker for dairy farmers over 200 DC doesn’t rely much on subsidies to get over the 20000€/year of the UK living wage (10-15% of the revenue is from subsidies). Dairy farmers under 200 DC can hardly stay over 20000€/year/family worker without subsidies and this even if they try to push the dairy cows’ yield.

We can see that the Agricultural Revenue comparison between farms seems relatively reasonable compared to the AV spread. This is due to how heavy are loan interest payments, rents and salaries, things that fueled the exogenous expansion of the farms.

Potato farming is very remunerating for farmers and they don’t depend a lot on subsidies to survive, giving farmers firm foundations to build up and expand in a very competitive market.

Every beef and sheep system is less profitable than milk production, nearly all of them are under 20,000€/family worker including subsidies from the CAP. The CAP payment represents from 50 to 100% of their agricultural revenue. Production systems producing store cattle are under the GlasTir scheme which allows them to get a higher amount of subsidies. Being able to fatten up beef allows a higher agricultural revenue. Generally the higher the LWG (Liveweight Gain) the better the agricultural revenue.

Finally support and rent-out farmers have an agricultural revenue between 10 and 20,000€, sometimes greater than corresponding beef and ovine systems. It stills depends heavily on the partner farms and how they are doing financially, and it mostly complements a retirement pension or another job.

In a nutshell

The diversity of landscape that can be found in Pembrokeshire gives different production potential. For example different LWG for the same cattle or different milk yield from the same acreage. From the farm archetypes we built we analysed the landscape of farming systems in Pembrokeshire. In Pembrokeshire the agricultural differentiation process has been dramatic. From 1945 to 1985 everything possible has been done to level up differences between farm types and get everyone to the same productivity level. From 1990 onwards, the liberalization of agricultural markets and quotas triggered a mass extinction among dairy farmers. Half of the small farms converted to beef. During the following years farmers responded to the input/output relation price squeeze: Some farmers are growing really big while others were looking for niche market or a market with some added value to be found. The location of the farm system had a big impact on what choice people could make and where they were able to go. Diversification in different production types has only been possible on Old Red Sandstone South and Limestone. Nowadays Pembrokeshire farming is a complex aggregate with farms working together between their outputs and inputs (rent-out land/rent-in or producing stores 12m old and using some…), a community which is more diverse and a lot smaller than 50 years ago. Diverse from an economic structure point of view, not only the gap between revenue, but also farmers’ age.

Problems faced:

- Concentration and amalgamation of farms and competitive land prices rendering the arrival of other actors challenging

- A sustained drive for farms to expand tremendously without limits and a concentration of the livestock in a small number of places with environmental consequences

- Added value producing systems that rely heavily on imported inputs but that sustain the farming community.

- Difficult access to GlasTir scheme compared to Tir Gofal: reserved for outstanding characters or very constraining options for short-term visibility. Fitting mainly retired people or farmers with ample land supply.